Crafting the Cask – Coopering from Tree to Barrel

Last time in Making whisky is all about the barrel right? we looked at the utility of barrels and why they’re made of oak, today we will be examining the coopers art and the process that a cask goes through in its journey from tree to being ready to mature whisky, rum, and all the things we love.

Who Started this Whole Thing?

The term ‘coopering’ is derived from the Latin ‘cupa’ or wooden vessel, but it was actually the Celts, not the Romans who are believed to be the pioneers of the art – a fact which only serves to add fuel to the fire on the debate about who first invented whisky. Origins aside, the distinctive shape of an oak cask is a perennial classic, providing enduring advantages of superior strength, large capacity, and manoeuvrability, the basic design has not been improved upon much since first conceived around 2,000 years ago. Back then, coopers were at the pinnacle of craftsmen and like masons commanded respect in society.

The Coopers Art

The challenge faced by a cooper is to make a standard oak barrel from 35-odd three foot long staves, fitting them together into a solid watertight container without glues, nails, or fillers. To do this each stave must be scalloped, curved on both sides, bevelled along both edges, and tapered at each end. Once this process was carried out entirely by hand using tools such as a crumming knife, trussing adze, and a roundshave, now days however much of the cutting and forming is carried out with the aid of specialised lathes and pneumatic presses.

After carefully crafting individual staves, the distinctive rounded belly shape of an oak cask must then be formed. Bending inch thick oak staves to the required shape without cracking or splitting requires heat and a fair amount of care. Traditionally one end of the staves would be bound together then placed upright around a brazier as the now malleable staves are slowly formed together as metal hoops are sequentially added to hold the taper. The cask is then inverted, and the process repeated on the other end.

From Tree to Plank

The coopers’ art isn’t the whole story though, to make a cask that doesn’t leak requires not only the great woodworking skills of the cooper but also great forestry work. An oak tree destined for casks must be split and treated in a very precise way.

Wood contains annual growth rings, vessels that can run perpendicular to the trunk known as xylem, and fibres that run up the length of the trunk – colloquially known as the grain. To account for these structural features and to produce suitable lengths of oak planks a tree must be cut in a much more elaborate way than what is acceptable for structural timber, which prioritises strength.

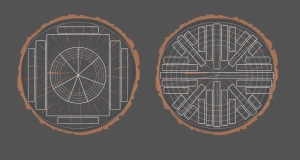

To achieve this a star shaped cut (as depicted below) is used to produce the maximum number of leak free staves from a single trunk.

A Standard Sawmill Cut (left) vs. the Barrel Starcut (right)

Each freshly cut stave will have fibres running along its whole length and vessels running across its width from edge to edge. Thus, barring the angels share which is a whole other can of worms, the spirit residing within a sealed barrel will not leak through the natural structures of the wood.

Prepping the Wood

After splitting, freshly cut oak planks must be dried to around 10% moisture to prevent warping and splitting both during coopering and once housing liquid. The importance of this process cannot be overstated and has had major impacts on world history, including (according to some historians) contributing greatly to Sir Francis Drake defeating the Spanish armada in 1588 – for more details see our previous blog post here.

For cheaper, mass produced casks the entire drying process has been industrialised, with large kilns used to dry freshly split oak planks in as little as a week.

For more premium oak casks a slower natural drying process is used that can take years. In this process, the roughly cut staves are neatly and loosely stacked outside a cooperage where the hot summer sun and warm zephyrs will cause sap to ooze out or the oak and winter rains will wash it way in repeated cycles. This produces finer and more gentle flavours in the oak the longer it is matured.

The slower natural drying process is used more commonly for French oak casks which commonly have staves that are around 20% thicker than similarly sized American oak casks. Obviously the longer the oak is weathered, the more expensive the cask will be, which accounts for some of the price disparity commonly seen between the two oak categories.